Chapter 2 Probability and Simulation

Optional Reading: R Cookbook Ch8 https://rc2e.com/probability

2.1 Review of Basic Probability

2.1.1 Random variables

A random variable is a numerical outcome produced by a random process.

- Toss a coin three times. The process is random, but once it happens, we can record a number, for example the number of heads.

- Measure the height of a randomly selected student.

- Record the waiting time until the next bus arrives.

Formally, a random variable is a function that assigns a number to each possible outcome of an experiment. In notation, \(X : \Omega \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\), where \(\Omega\) is the sample space (set of all possible outcomes).

Practically, in data science, it is just a numerical quantity whose value is uncertain before observation.

In R, A vector like x <- rnorm(1000) can be thought of as 1000 realizations of the same random variable.

2.1.2 Distribution functions

The distribution function (or cumulative distribution function, CDF) of a random variable \(X\) is \[\begin{equation*} F(x) = P(X \leq x). \end{equation*}\]

What it tells you:

For any cutoff value \(x\), it gives the probability that \(X\) is at or below \(x\).

It fully describes how the values of \(X\) are distributed.

Probabilities of intervals come from differences: \[\begin{equation*} P( a < X \leq b) = F(b) - F(a). \end{equation*}\]

In practice:

Empirical distribution function (EDF) can be used to estimate the CDF of data.

In R, ecdf(x) constructs the EDF (will see it later).

2.1.3 Density function (pdf)

A density function (density) describes how concentrated the probability is around different values.

For a continuous random variable \(X\), a function \(f(x)\) is a density if \[\begin{equation*} P( a < X \leq b) = \int^b_a f(x) dx. \end{equation*}\]

Note:

- \(f(x)\) itself is not a probability.

- Probabilities come from areas under the curve, not from heights.

- It is normal for \(f(x)\) to be larger than 1.

Relationship with the CDF:

The CDF is the integral of the density: \[\begin{equation*} F(x) = \int^x_{-\infty} f(t)dt. \end{equation*}\]

When differentiable, the density is the derivative of the CDF.

In practice:

Histograms and kernel density plots are estimates of the density.

In R, density(x) computes a smooth density estimate.

2.1.4 Probability mass function (PMF)

A probability mass function (PMF) describes how probability is assigned to discrete outcomes.

For a discrete random variable \(X\), the PMF is the function \[\begin{equation*} p(x) = P(X = x). \end{equation*}\]

What it tells you:

- which values of \(X\) are possible,

- how likely each value is,

- all probabilities are nonnegative and add up to 1.

In contrast to a density function:

- a PMF assigns probability directly to individual values,

- probabilities are obtained by summation rather than integration.

Simple example: rolling a die

Let \(X\) be the outcome when rolling a fair six-sided die.

- The possible values are \(1,2,3,4,5,6\).

- Each outcome has probability \(1/6\).

The PMF is \[\begin{equation*} p(x) = \begin{cases} 1/6, & x = 1,2,3,4,5,6, \\ 0, & \text{otherwise}. \end{cases} \end{equation*}\]

From the PMF, probabilities of events are computed by summing: \[\begin{equation*} P(X \text{ is even}) = p(2) + p(4) + p(6) = \frac{1}{2}. \end{equation*}\]

Relationship to the distribution function

For a discrete random variable, \[\begin{equation*} F(x) = P(X \le x) = \sum_{u \le x} p(u). \end{equation*}\]

This shows that the distribution function accumulates probability from the PMF, and that the PMF corresponds to the jumps of the distribution function.

PMFs in data science

PMFs commonly arise when modeling:

- counts (number of clicks, events, or failures),

- discrete simulation outputs,

- categorical outcomes represented numerically.

In practice, PMFs are often estimated by relative frequencies and visualized using bar plots.

2.1.5 Quantile function

The quantile function answers the inverse question of the CDF:

“At what value does the random variable reach a given probability level?”

Formally, the quantile function is

\[\begin{equation*} Q(p) = \inf \{x : F(x) \geq p\}, \quad p \in (0, 1). \end{equation*}\] Examples:

The median is \(Q(0.5)\).

The 90th percentile is \(Q(0.9)\).

Why quantiles are important in data science?

Robust summaries

The median (50th percentile) is robust to outliers, unlike the mean.

Interquartile range (IQR) measures spread without being influenced by extreme values.

Many real-world variables (income, response times, network traffic) are highly skewed. Quantiles remain stable even when the distribution is skewed or heavy-tailed. Quantiles describe such distributions more meaningfully than mean and variance.

2.2 Simulation

Simulation is the use of a computer to repeatedly imitate the behavior of a system that involves randomness.

The system can be simple or complex. It may involve:

one or many random variables,

multiple interacting components,

time evolution,

decision rules or algorithms,

unknown quantities that we want to understand.

To carry out a simulation, we do three things:

Specify a data-generating mechanism. We describe how randomness enters the system and how different variables are produced or interact. This may involve probability distributions, dependence structures, or procedural rules.

Generate synthetic data by repeated runs The computer repeatedly runs the mechanism, each time producing an artificial realization of the system.

Summarize and analyze the outcomes We use the simulated data to approximate probabilities, study variability, evaluate methods, or understand long-run behavior.

Simulation is especially useful when:

analytically calculations are difficult or impossible,

the system is high-dimensional or nonlinear,

we want to understand uncertainty, not just averages.

In data science, simulation is used to:

approximate probabilities and expectations,

assess the performance of statistical methods,

study the effect of model assumptions,

explore “what-if” scenarios.

Conceptually, simulation replaces mathematical derivations with repeated computational imitation of the system under study.

2.2.1 A simple example: probability of an even number when rolling a die

Consider rolling a fair six-sided die.

The system is the act of rolling the die.

The data-generating mechanism assumes that each outcome \(1,2,\ldots,6\) occurs with equal probability.

The event of interest is rolling an even number, that is, \({2,4,6}\).

Analytically, the probability of an even number is \[\begin{equation*} P(even) = \frac{3}{6} = \frac{1}{2}. \end{equation*}\] Using simulation:

we let the computer imitate rolling the die many times,

record each outcome,

and compute the proportion of rolls that are even.

This proportion is a Monte Carlo approximation to the true probability. As the number of simulated rolls increases, the simulated proportion gets closer to \(1/2\).

2.3 Probability Distributions in R

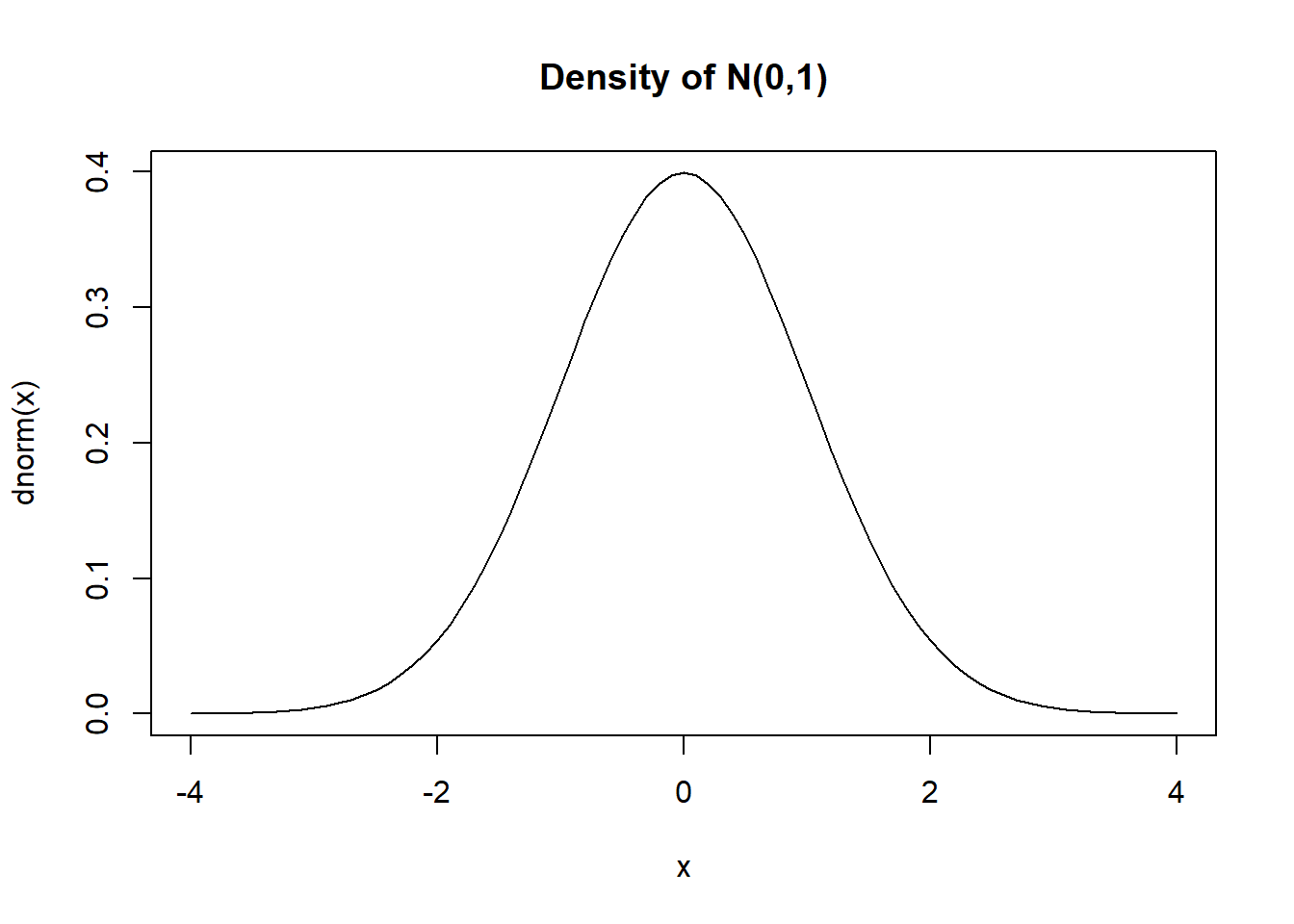

Using the normal distribution as an example:

| Function | Purpose |

|---|---|

dnorm |

Normal density |

pnorm |

Normal CDF |

qnorm |

Normal quantile function |

rnorm |

Normal random variables |

Examples

Density of \(N(2, 3^2)\) at \(5\).

\(P(X \leq 3)\), where \(X \sim N(2, 3^2)\)

pnorm(3, mean = 2, sd = 3)

## [1] 0.6305587

# "mean =" and "sd =" are optional

pnorm(3, 2, 3)

## [1] 0.6305587Generate 10 random variables, each follows \(N(3, 4^2)\).

rnorm(10, 3, 4)

## [1] 1.67465435 0.03941654 5.52902993 1.15437973 7.03316753

## [6] 9.90674845 2.60383555 4.89579559 6.59485994 -2.4023708595th percenttile of \(N(0, 1)\). Find \(q\) such that \(P(Z \leq q) = 0.95\)

Plotting the normal density

2.3.1 Common Distributions

| Discrete distribution | R name | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Binomial | binom |

n = number of trials; p = probability of success for one trial |

| Geometric | geom |

p = probability of success for one trial |

| Negative binomial (NegBinomial) | nbinom |

size = number of successful trials; either prob = probability of successful trial or mu = mean |

| Poisson | pois |

lambda = mean |

| Continuous distribution | R name | Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Beta | beta |

shape1; shape2 |

| Cauchy | cauchy |

location; scale |

| Chi-squared (Chisquare) | chisq |

df = degrees of freedom |

| Exponential | exp |

rate |

| F | f |

df1 and df2 = degrees of freedom |

| Gamma | gamma |

rate; either rate or scale |

| Log-normal (Lognormal) | lnorm |

meanlog = mean on logarithmic scale; sdlog = standard deviation on logarithmic scale |

| Logistic | logis |

location; scale |

| Normal | norm |

mean; sd = standard deviation |

| Student’s t (TDist) | t |

df = degrees of freedom |

| Uniform | unif |

min = lower limit; max = upper limit |

To get help on the distributions:

?dnorm

?dbeta

?dcauchy

# the following distributions need to use different code

?TDist

?Chisquare

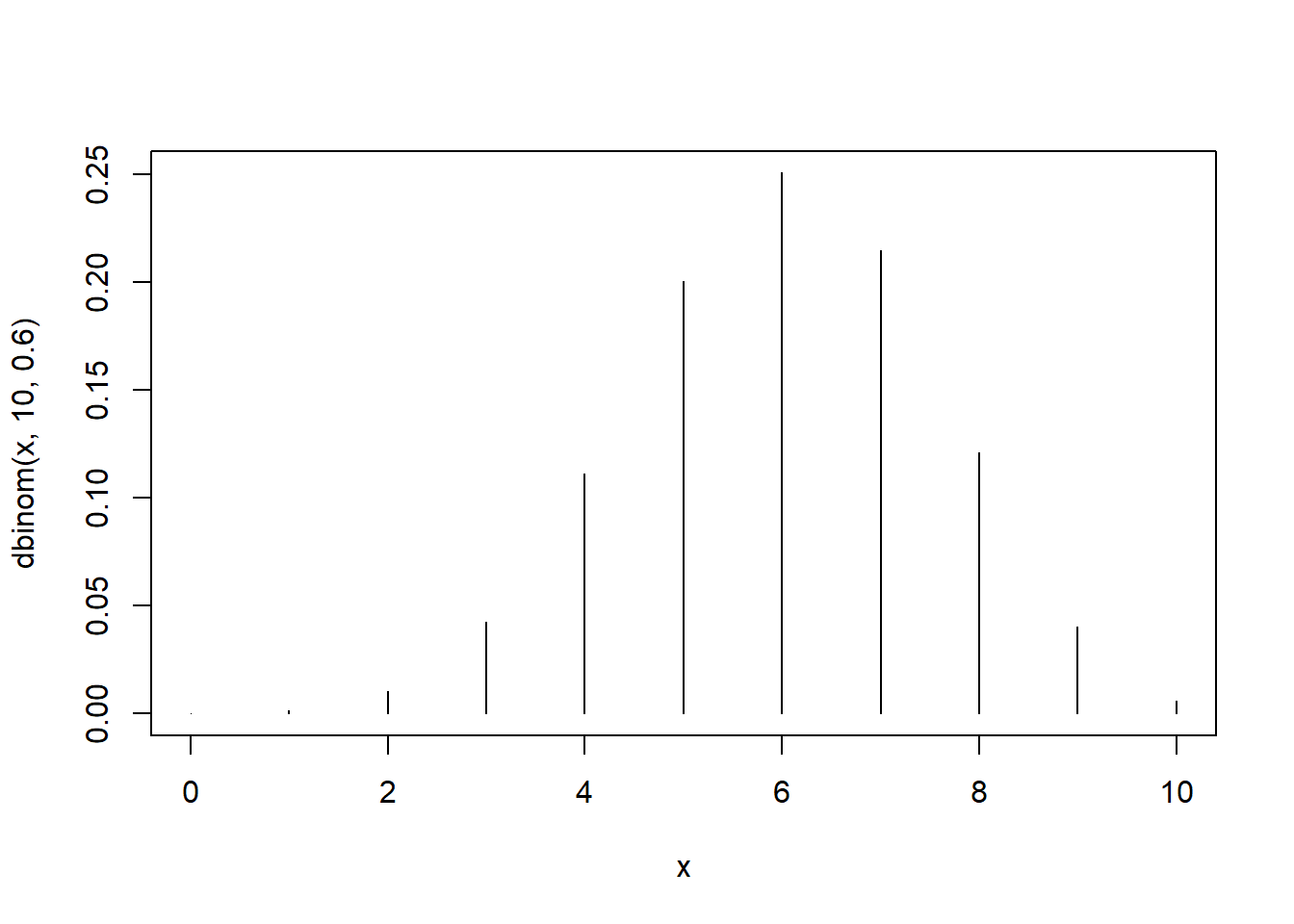

?LognormalExamples (Using Binomial as an Example)

dbinom(2, 10, 0.6) # p_X(2), p_X is the pmf of X, X ~ Bin(n=10, p=0.6)

## [1] 0.01061683

pbinom(2, 10, 0.6) # F_X(2), F_X is the CDF of X, X ~ Bin(n=10, p=0.6)

## [1] 0.01229455

qbinom(0.5, 10, 0.6) # 50th percentile of X

## [1] 6

rbinom(4, 10, 0.6) # generate 4 random variables from Bin(n=10, p=0.6)

## [1] 7 6 9 5

x <- 0:10

plot(x, dbinom(x, 10, 0.6), type = "h") # "h" for histogram like vertical lines

2.3.2 Exercises

- The average number of trucks arriving on any one day at a truck depot in a certain city is known to be 12. Assuming the number of trucks arriving on any one day has a Poisson distribution, what is the probability that on a given day fewer than 9 (strictly less than 9) trucks will arrive at this depot?

- Let \(Z \sim N(0, 1)\). Find \(c\) such that

- \(P(Z \leq c) = 0.1151\)

- \(P(1\leq Z \leq c) = 0.1525\)

- \(P(-c \leq Z \leq c) = 0.8164\).

# P(0 <= Z <= c) = 0.8164/2

# P(Z <= c) = 0.8164/2 + 0.5

c <- qnorm(0.8164 / 2 + 0.5)

# test our answer

pnorm(c)- pnorm(-c)

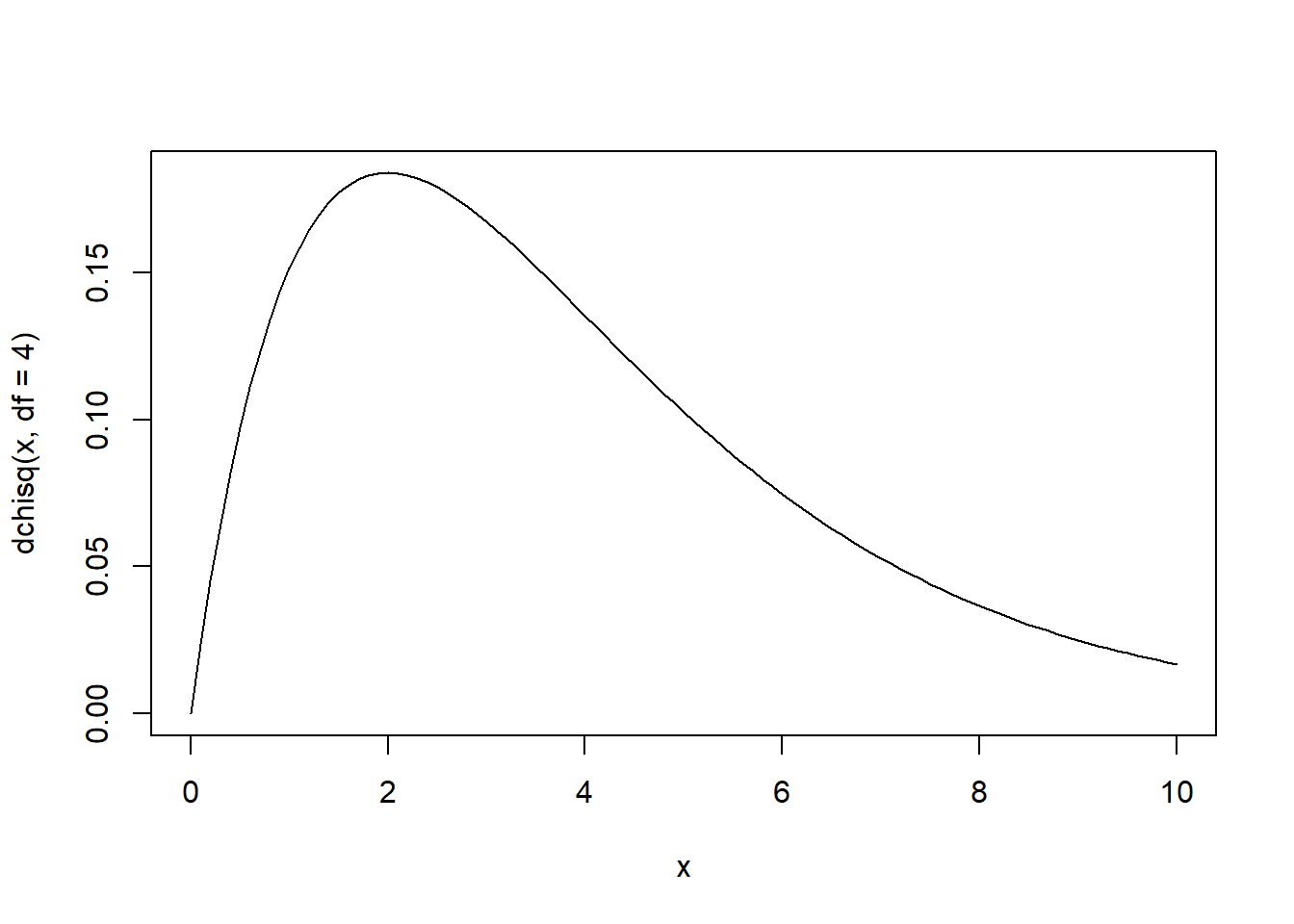

## [1] 0.8164- Plot the density of a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom \(4\), from \(x=0\) to \(x=10\).

- Find the 95th percentile of this distribution.

# note that a chi-squared r.v. is nonnegative

x <- seq(0, 10, by = 0.1)

plot(x, dchisq(x, df = 4), type = "l")

- Simulate \(10\) Bernoulli random variables with parameter \(0.6\).

- Plot the Poisson pmf with parameter \(2\) from \(x = 0\) to \(x = 10\).

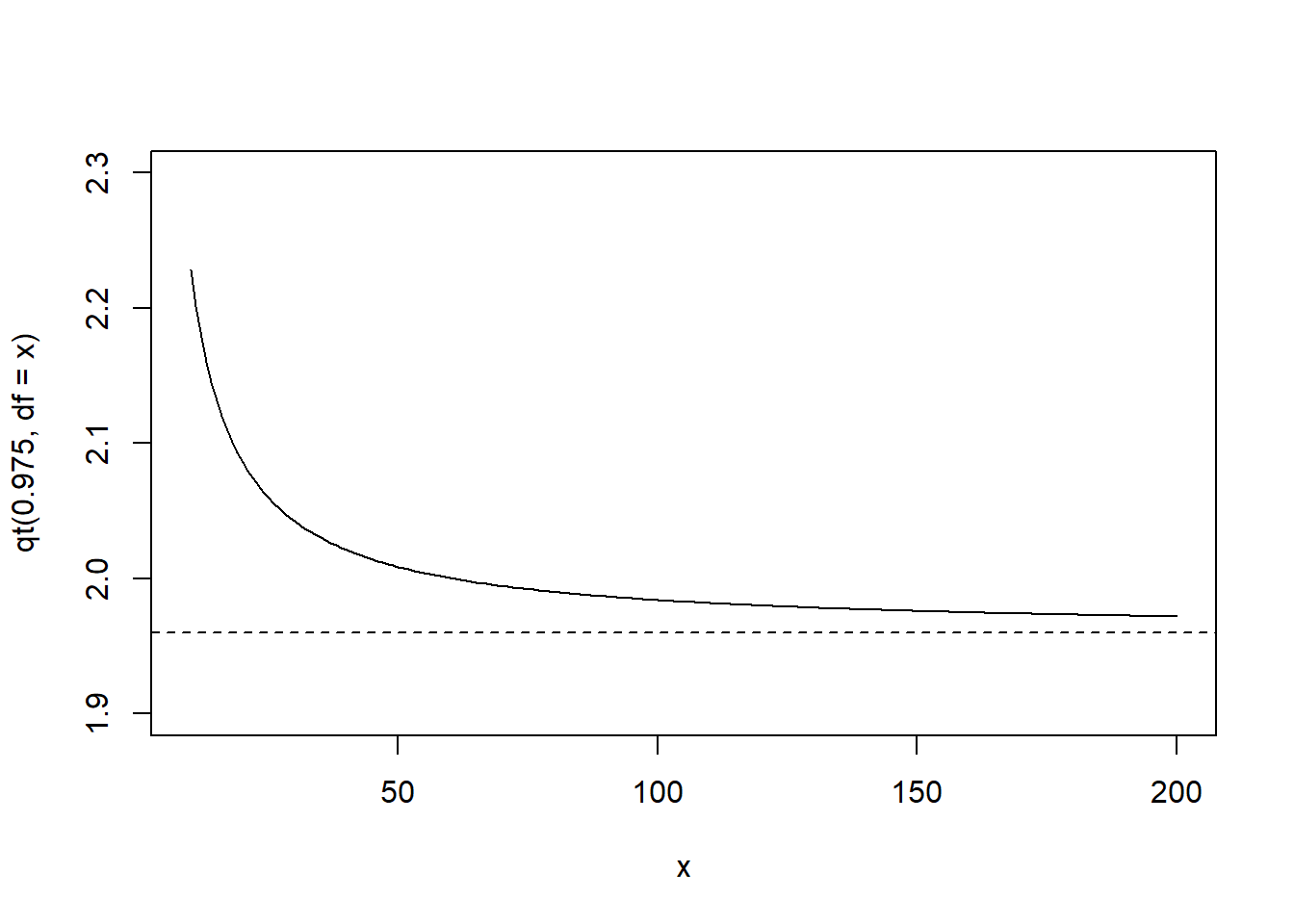

- Draw a plot to illustrate that the 97.5th percentile of the t distribution will be getting closer to that of the standard normal distribution when the degrees of freedom increases.

x <- 10:200

plot(x, qt(0.975, df = x), type = "l", ylim = c(1.9,2.3))

# add a horizontal line with value at qnorm(0.975)

# lty = 2 for dashed line, check ?par

abline(h = qnorm(0.975), lty = 2)

2.4 Simulation in R

We have already seen how to use functions like

runif(),rnorm(),rbinom()to generate random variables.In reality, these numbers are not truly random. They are generated by a deterministic algorithm called a pseudo-random number generator. Conceptually, it works like this:

Start from an initial value called the seed.

Apply a fixed mathematical rule to produce the next number.

Use that number to produce the next one.

Repeat.

Thus, the sequence is completely determined once the seed is fixed.

set.seed()tells R the value of the seed in that algorithm.The pseduo-random number sequence will be the same if it is initialized by the same seed. This makes your work: reproducible, easier to debug, easier to share with others.

# every time you run the first two lines, you get the same result

set.seed(1)

runif(5)

## [1] 0.2655087 0.3721239 0.5728534 0.9082078 0.2016819

# every time you run the following code, you get a different result

runif(5)

## [1] 0.89838968 0.94467527 0.66079779 0.62911404 0.06178627Sampling from discrete distributions

Usage of sample():

sample(x, size, replace = FALSE, prob = NULL)

See also ?sample.

sample(10) # random permutation of integers from 1 to 10

## [1] 3 1 5 8 2 6 10 9 4 7

sample(10, replace = T) # sample with replacement

## [1] 5 9 9 5 5 2 10 9 1 4

sample(c(1, 3, 5), 5, replace = T)

## [1] 5 3 3 3 3

# simulate 20 random variables from a discrete distribution

sample(c(-1,0,1), size = 20, prob = c(0.25, 0.5, 0.25), replace = T)

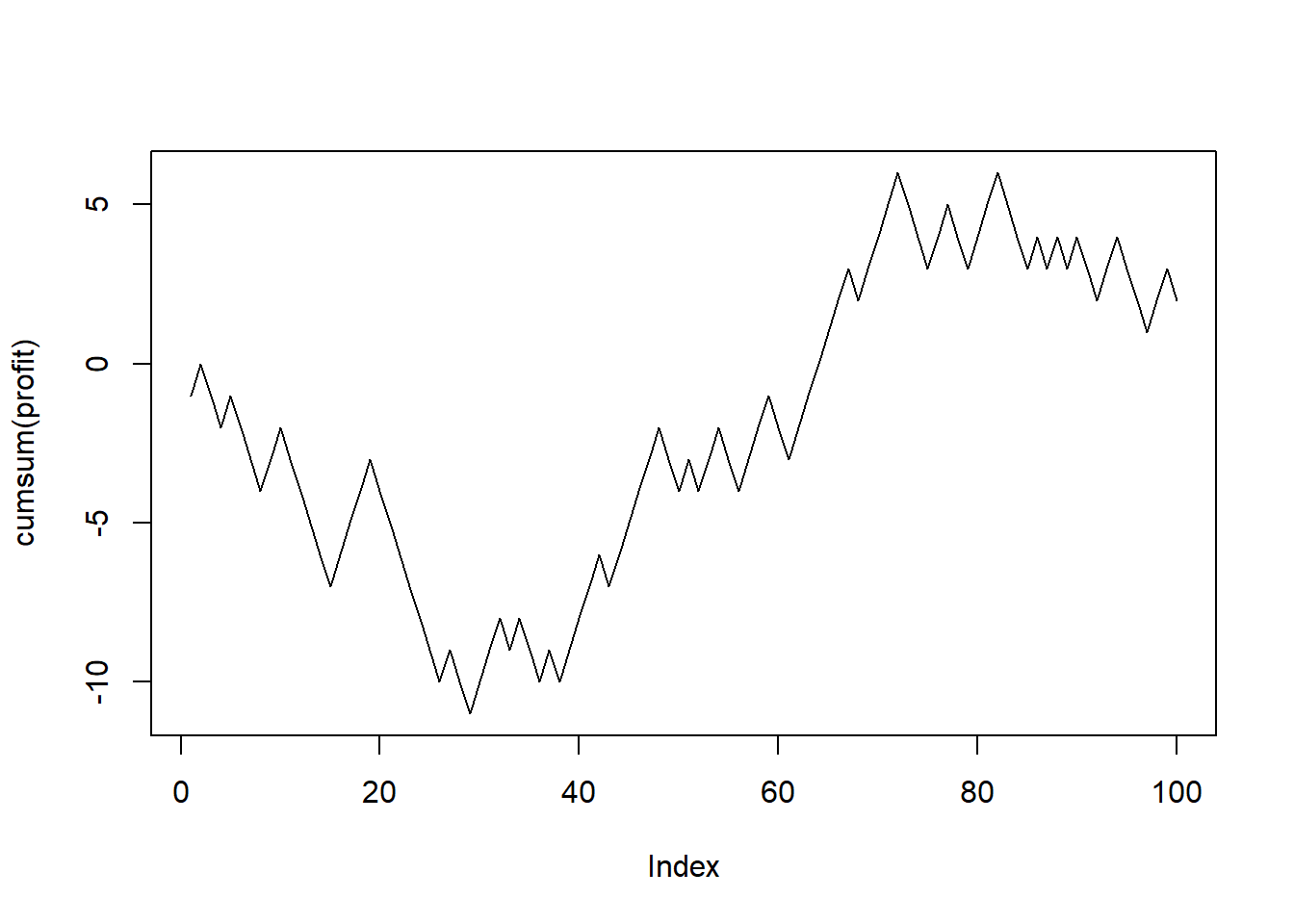

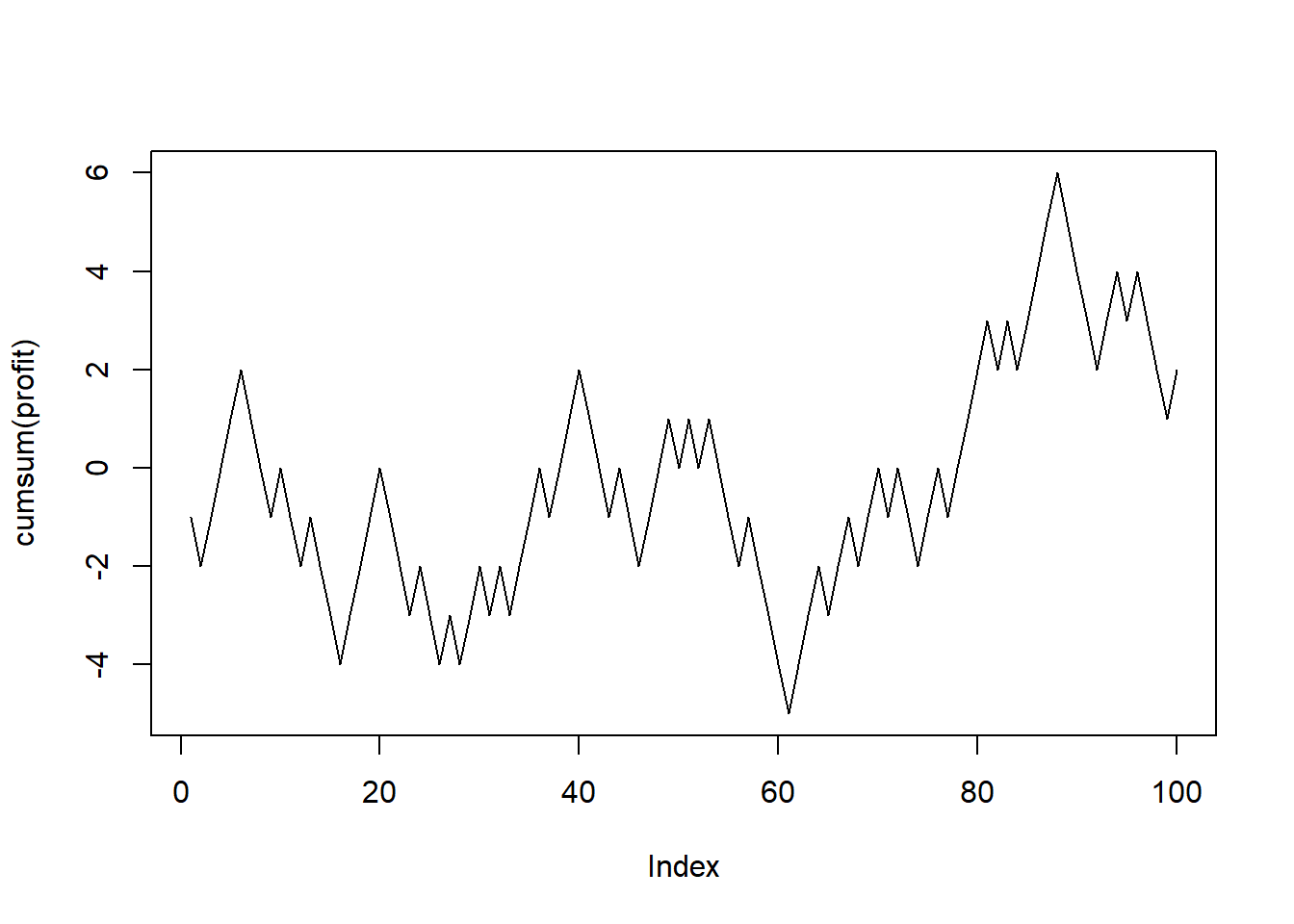

## [1] -1 1 1 -1 0 0 1 1 0 -1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 -1 0Example: Suppose we have a fair coin and we play a game. We flip the coin. We win $1 if the result is head and lose $1 if the result is tail. You play the game 100 times. You are interested in the cumulative profit.

set.seed(1) # R actually generates pseudo random numbers

# setting the seed ensure that each time you will get the same result

# for illustration, code debugging, reproducibility

profit <- sample(c(-1, 1), size = 100, replace = T)

plot(cumsum(profit), type = "l")

Example: You have two dice \(A\) and \(B\). For die \(A\), there are \(6\) sides with numbers \(1,2,3,4,5,6\) and the corresponding probability of getting these values are \(0.1,0.1,0.1,0.1,0.1,0.5\). For die \(B\), there are \(4\) sides with numbers \(1,2,3,7\) and the corresponding probability of getting these values are \(0.3,0.2,0.3,0.2\). You roll the two dice independently. Estimate \(P(X > Y)\) using simulation, where \(X\) is the result from die \(A\) and \(Y\) is the result from die \(B\).

n <- 10000 # number of simulations

X <- sample(1:6, size = n, replace = TRUE, prob = c(0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.5))

Y <- sample(c(1, 2, 3, 7), size = n, replace = TRUE, prob = c(0.3, 0.2, 0.3, 0.2))

mean(X > Y)

## [1] 0.6408Why the sample mean approximates the required probability? Recall the strong law of large numbers (SLLN). Let \(X_1,\ldots,X_n\) be independent and identically distributed random variables with mean \(\mu:=E(X)\). Let \(\overline{X}_n:= \frac{1}{n} \sum^n_{i=1}X_i\). Then

\[\overline{X}_n \stackrel{a.s.}{\rightarrow} \mu.\]

Note: a.s. means almost surely. The above convergence means \(P(\lim_{n\rightarrow \infty} \overline{X}_n = \mu) = 1\). Note that (the expectation of an indicator random variable is the probability that the corresponding event will happen)

\[ P(X>Y) = E(I(X>Y)).\]

To apply SLLN, we just need to recognize the underlying random variable is \(I(X>Y)\). Then, with probability \(1\), the sample mean

\[ \frac{1}{n} \sum^n_{i=1} I(X_i > Y_i) \rightarrow P(X>Y).\]

The quantity on the LHS is what we compute in mean(X > Y) (note that we are using vectorized comparison).

2.5 Additional Exercises

Ex 1

Let \(X \sim N(mean = 2, sd = 1)\), \(Y \sim Exp(rate = 2)\), \(Z \sim Unif(0, 4)\) (continuous uniform distribution on [0,4]). Suppose \(X, Y, Z\) are independent. Estimate \(P(\max(X,Y)>Z)\).

Recall the difference between pmax and max:

# always try with simple examples when you test the usage of functions

x <- c(1, 2, 3)

y <- c(0, 5, 10)

max(x, y)

## [1] 10

pmax(x, y)

## [1] 1 5 10Answer:

n <- 100000

x <- rnorm(n, 2, 1)

y <- rexp(n, 2)

z <- runif(n, 0, 4)

mean(pmax(x, y) > z)

## [1] 0.51129Ex 2

Let \(X \sim N(mean = 2, sd = 1)\), \(Y \sim Exp(rate = 2)\), \(Z \sim Unif(0, 4)\) (continuous uniform distribution on [0,4]). Suppose that \(X, Y, Z\) are independent. Estimate \(P(\min(X,Y)>Z)\).

n <- 100000

x <- rnorm(n, 2, 1)

y <- rexp(n, 2)

z <- runif(n, 0, 4)

mean(pmin(x, y) > z) # what is the difference between pmin and min?

## [1] 0.11283Ex 3

Let \(X \sim N(mean = 2, sd = 1)\), \(Y \sim Exp(rate = 2)\), \(Z \sim Unif(0, 4)\) (continuous uniform distribution on [0,4]). Suppose that \(X, Y, Z\) are independent. Estimate \(P(X^2 Y>Z)\).

n <- 100000

x <- rnorm(n, 2, 1)

y <- rexp(n, 2)

z <- runif(n, 0, 4)

mean(x ^ 2 * y > z)

## [1] 0.4084Ex 4

Person \(A\) generates a random variable \(X \sim N(2, 1)\) and Person \(B\) generates a random variable \(Z \sim Unif(0, 4)\). If \(X < Z\), Person \(A\) will discard \(X\) and generate another random variable \(Y \sim Exp(0.5)\). Find the probability that the number generated by \(A\) is greater than that by \(B\).

n <- 100000

x <- rnorm(n, 2, 1)

y <- rexp(n, 0.5)

z <- runif(n, 0, 4)

mean(pmax(x, y) > z)

## [1] 0.63853We will see additional simulation examples after we talk about some programming in R

There are many important topics that we will not discuss

- algorithms for simulating random variables

- inverse transform

- acceptance rejection

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo

- methods to reduce variance in simulation

- Control variates

- Antithetic variates

- Importance sampling